Matteo Ricci's World Map and the Manchus

Florin-Stefan Morar

Scroll Down

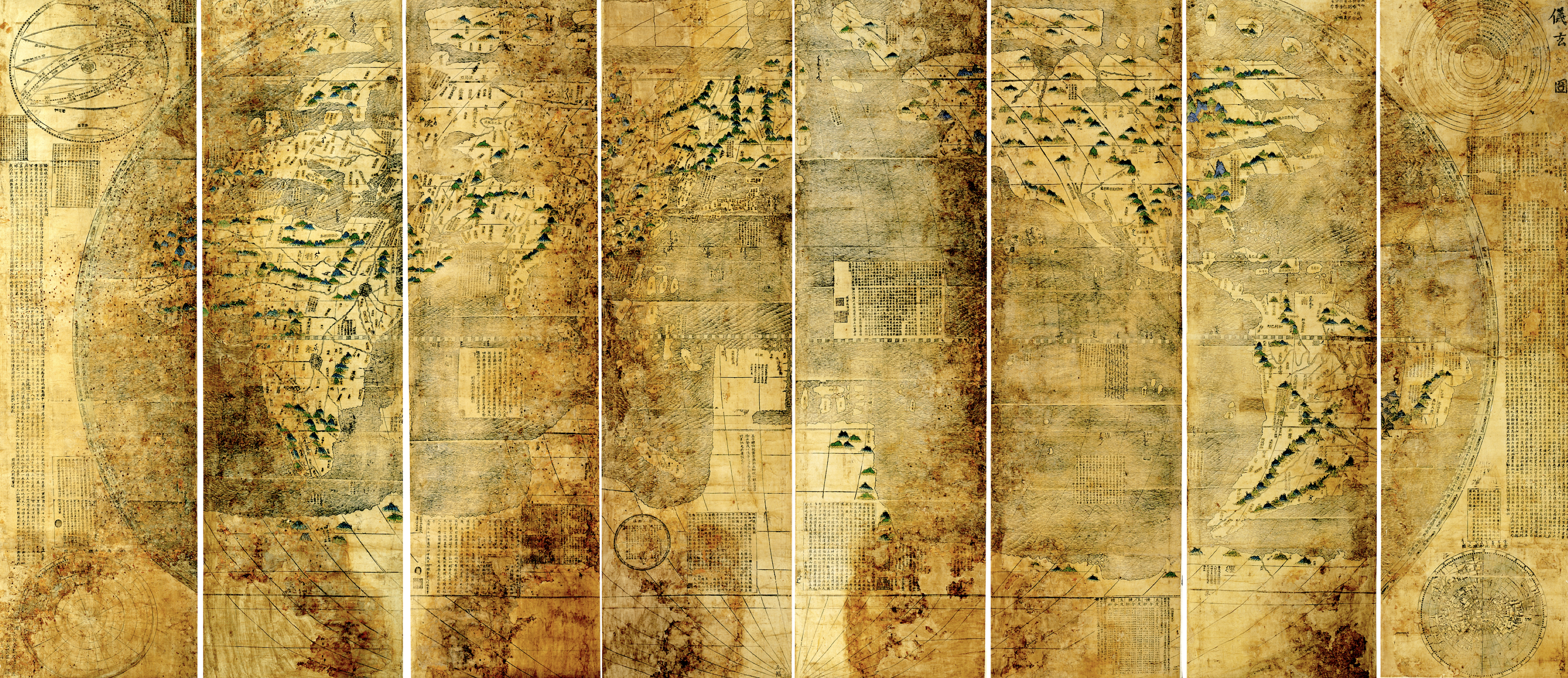

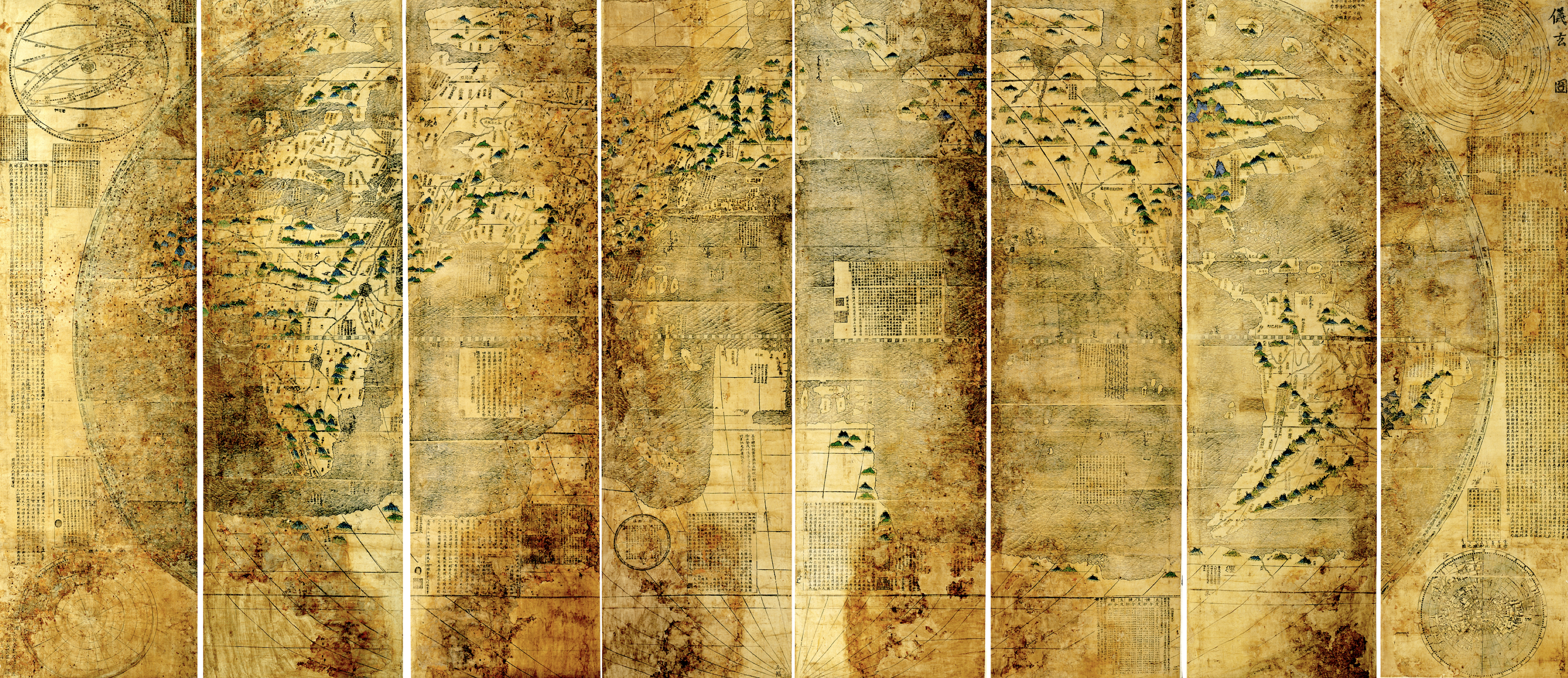

The Map of Observing the Mysteries of the Heaven and Earth (Liangyi xuanlan

tu 兩儀玄覽圖 ), which we call here the Xuantu is a worldmap

in eight panels created in 1603 by the Ming dynasty

military official Li Yingshi李應試.

Figure 1: Map of Observing the Mysteries of the Heaven and the Earth. Liaoning Provincial Museum辽宁省博物馆, Shenyang, People's Republic of China

There is strong reason to believe that

the Manchus obtained this particular map before they conquered China, a surprising

development that makes us reconsider the Manchus' relationship to Western

cartography.

This interactive websiste will tell the

story of this maps and presents some of the evidence linking the Xuantu map to the pre-

conquest Manchus

Matteo Ricci and the scholar Li Zhizao 李之藻 created in 1602 a map named Complete Map of the Myriad Kingdoms of the World ( Kunyu Wanguo Quantu 坤輿萬國全圖).

It included geographical descriptions of the historical five continents, complete with place-names, a précis of Ptolemaic cosmology, and paper instruments for measuring polar altitude and latitude.

Figure 2: Map of myriad countries of the Earth, Kunyu wanguo quantu 坤輿萬國全圖, by Matteo Ricci, Li Zhizao 李之藻, et al., 1602. James Ford Bell Library, University of Minnesota.

The Xuantu is a large object, measuring 2 meters (78.74 inches) vertically and 4.42 meters (174.01 inches) horizontally. As such, it fits awkwardly among Chinese prints from the Ming dynasty. Maps of this size meant for a high-end audience of officials were rarely prints. Instead, just as for paintings, Chinese artisans normally used silk, which was favored for its superior durability. Silk, however, because of its cost, was more appropriate for the creation of unique items, such as decorative folding screens.

For Sino-Western world maps, the desire to quickly disseminate many copies trumped that of creating solid, durable objects. World maps by Matteo Ricci and other Jesuits thus came to occupy an important niche. They were as large in size as silk maps made for important people, yet easily reproducible and affordable. This was at the root of their success in the late Ming. It is also the reason why so few copies survived: large prints were fragile.

Folding screen with figures in a landscape, Qing dynasty, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

Indeed, Xuantu is important not so much for what it has in it but for what it has on it: the repairs, modifications, and annotations added to the original print.

Material alterations, the content of annotations, and the form of the Manchu script are three aspects that demonstrate the epistemological engagement of the Manchu translators of the Later Jin state with the Map of Observing the Mysteries of the Heaven and Earth.

The Map of Observing Mysteries, like its 1602 predecessor, the Map of Myriad Kingdoms, was intended by Ricci to be colored by hand, to better distinguish the continents and land masses from the bodies of water. Since the coloring process had to be done after the printing and involved the work of another specialized artisan, incurring additional expenses, many copies remained black-and-white prints. The Shenyang copy was originally uncolored. Yet during its life in the Shenyang palace, an artisan was tasked with embellishing the mountain ranges across all the continents in the style of Chinese painting. The color scheme of these decorations—blue, green, and gold—fits the one used throughout the Shenyang palace.

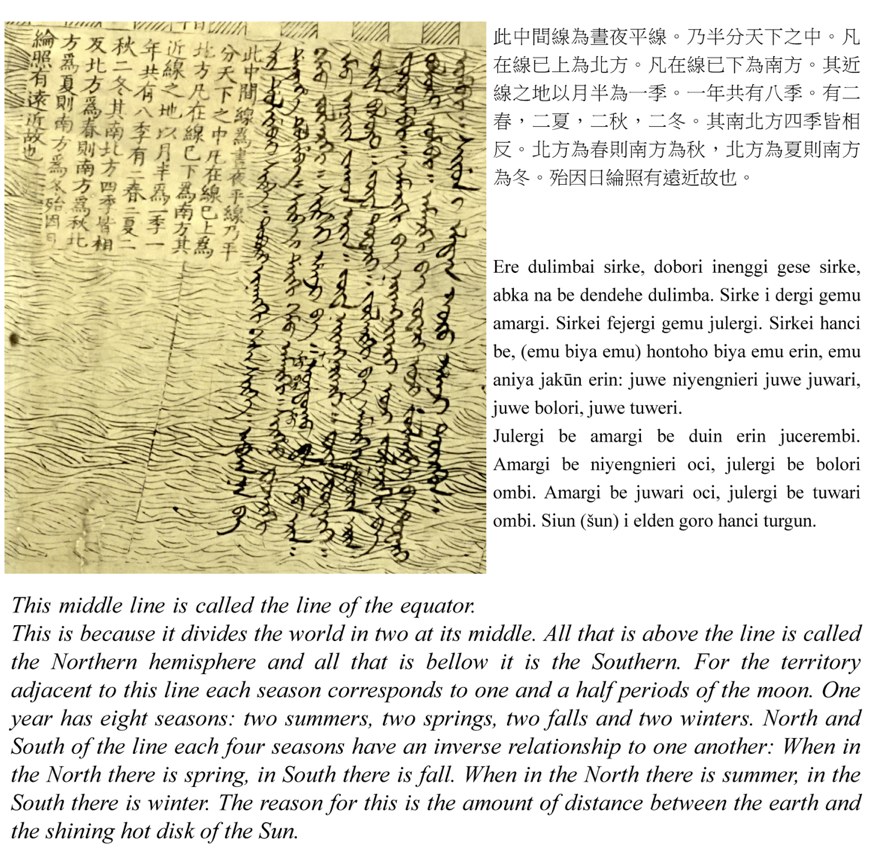

Besides the repairs and added decorative elements, the Shenyang copy of the Map of Observing Mysteries displays a number of Manchu annotations. These inscriptions consisted of both topology and technical elements. The technical elements included the cosmological theory explained in the map's prefaces and surrounding texts. The theory of the map expounded in the preface by Matteo Ricci presented relationships between Earth's spherical shape, its position in the solar system, and the cycles of night and day. All of these features, represented by lines on the map, had Manchu translations attached.

The central text of the map summarized the cosmology in a commentary written in Manchu placed on the map near the line of the equator. The main divisions of Earth into continents and oceans, described in the preface by Ricci and other texts on the map, were also translated.

Taken together, they suggest that the Manchu translator had a grasp of and an interest in the “theory” of the map, having read and understood the prefaces and other accompanying texts.

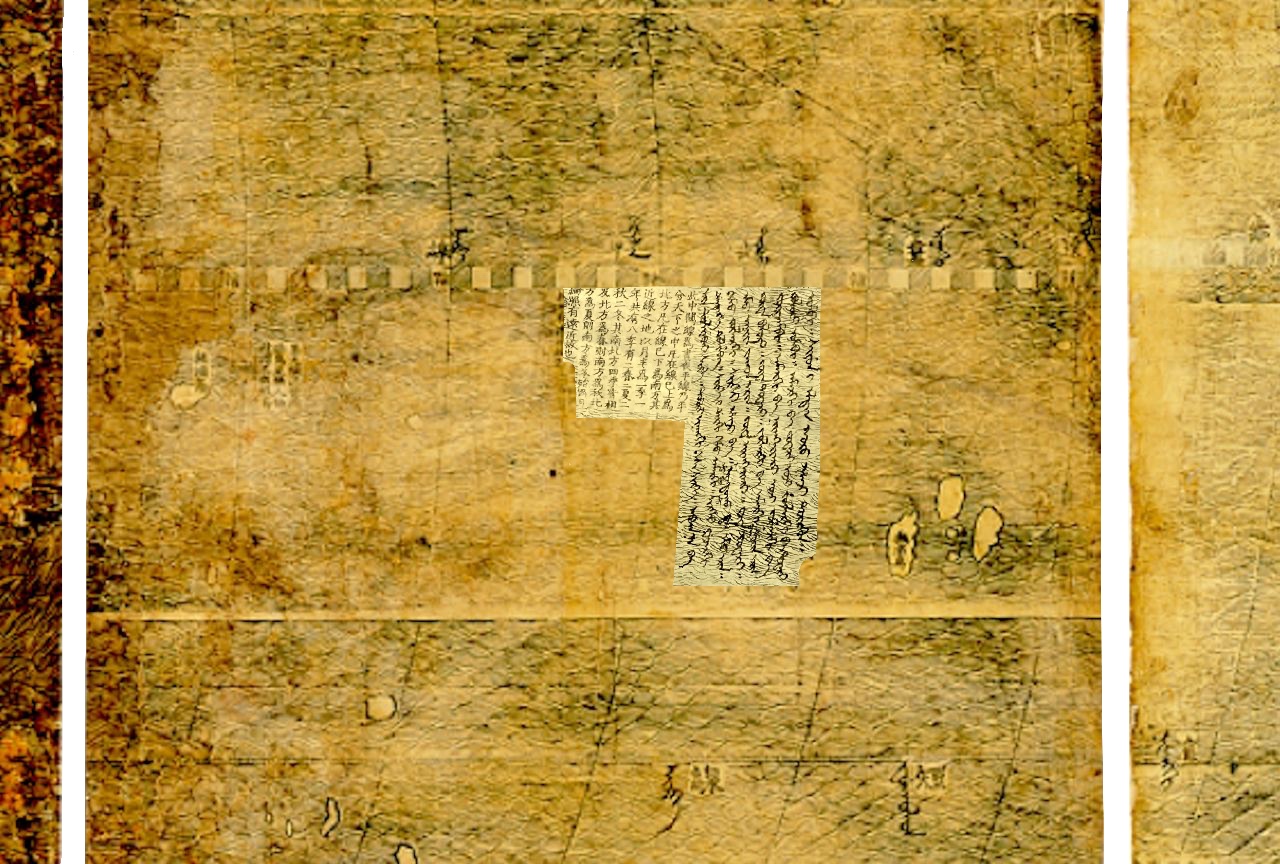

There are three things that make us believe that this map stood out at its time. It was repaired, intentionally colored, and had inscriptions of the Manchu transcript on it. When it was used in the Shenyang palace, the Xuantu was damaged. Winters in Shenyang are bitterly cold, and rooms must be heated. For this reason, there was a temperature difference between the upper and lower parts of the room. This created condensation, and because the map was most likely displayed vertically, the dampness damaged the portions closer to the ground.

The bottom corner of the eight roll (left side of the map) of the Shengyang copy of the Map of observing mysteries. This area, representing the Southern Hemisphere, was damaged and later repaired. An artisan had applied paper paste and, after it dried, redrew the meridians to give the impression of continuity. Further damage to the map reveals the discrepancy between the two layers.

The amount of information included in the reconstruction on the top stratum differed from that of the layer below. This was due perhaps to the artisan's limited knowledge. But it might also be a reflection of the interests of the map owners. he Southern Hemisphere on the left side of the map (roll one), for instance, disappeared completely, being covered up in the restoration; only a circle and some of the radiating meridians were copied on top for consistency. On the other hand, the northern hemisphere was preserved, and annotations were added to it because it encompassed places the Manchus were interested in.

Most translations of place-names are concentrated in

East Asia, radiating toward Europe.The Manchus, it seems, were primarily preoccupied with

locating themselves and their immediate surroundings; in terms of their outward interest, they

focused on looking westward.

The Manchu homeland is marked out by the translation of three adjacent place-names

northeastof the Great Wall: Jurchen (Nüzhen女真), Mount Changbai (Changbai Shan長白山), and the City

of the Five Nations (Wuguo Cheng五國城).

The translation of Mount Changbai (Changbai Shan長白山), on the other hand, is more revealing of the Manchus' own emerging sense of identity in the sixteenth century. The mountain, appearing here in translation as Sanggiyan Alin, was part of an imperial cult throughout the Qing, revered as the birthplace of the mythical founder of the dynasty, Bukūri Yongšon. The addition of an in-scription alongside the mountain is an indication that the place was meaningful for the Manchus as early as the Later Jin.

Moving beyond this sphere, immediately neighboring countries such as Japan, Korea, and the Great Ming are labeled using names of Manchu origin: Ose, Sohlo, and Nikan. These names do not describe places or countries but, rather, ethnicities.They were well established in the common geographic knowledge embedded in the Manchu language, as the Manchus had direct interactions with them.

The rest of the translations of place-names on the map are transliterations in Manchu of the pronunciation of Chinese characters. These include the place-names for India, the Philippines, Java, Madagascar, the Cape of Good Hope, the Fortunate (Canary) Islands, Greenland,and Novaya Zemlya. The selection of these places cannot be easily explained by what we readily know about the Manchus. However, since they were singled out among all the other locations on the map, we must assume that they triggered a sense of relevance and recognition for the translator and for the map's viewership.

The translations of places like the Fortunate Islands, the Cape of Good Hope, Madagascar, Java, and the Philippines resulted from an awareness of the centers of the European trade network around Eurasia. These were, after all, places from which ships dropping anchor at Macao would have been coming.

However, the form of the inscriptions is also meaningful. They can help answer questions about the dating and authorship of the translations.

According to the Manchu Veritable Records,

the Manchu written language was a direct invention of bilingual scholars working for Nurhaci and

was established in 1599.

A well-known passage describes how Nurhaci noticed that Mongolian and

Chinese could be both written and spoken, while the Manchus needed to use Mongolian—a language

they did not speak as natives—to write documentsand proclamations. Consequently, Nurhaci asked

the polyglot scholar Erdeni and the judge Gagai to solve the problem and modify the Mongolian

script so as to write Manchu words. But because Mongolian letters could not perfectly represent

Manchu sounds, this version of the scripthad a few drawbacks. The script could not clearly

distinguish a and e,o and u, or k,g, and h. There was also no distinction between front and back

d and t, and there were uncertainties in spelling certain words.

A reform of the language that would address these issues was implemented during the time of the second Khan, Hong Taiji. The most important and visible aspect of this reform was the addition of dots and circles to solve the problem of distinction. The addition of dots could separate a from e,o from u, and k from g, while circles would distinguish k from h. This way of writing Manchu achieved virtually universal usage and has remained the standard way of writing it to this day.

Analysis of the form of the script on the map thus indicates that the Map of Observing Mysterieswas translated between roughly 1625 and 1636, when the reformed version of the Old Manchu script was used. In any case, the map's annotations indicate an interest in, as well as an epistemological engagement with, a Sino-Western artifact in a crucial moment, as the Manchus were beginning to plan their conquest of China.

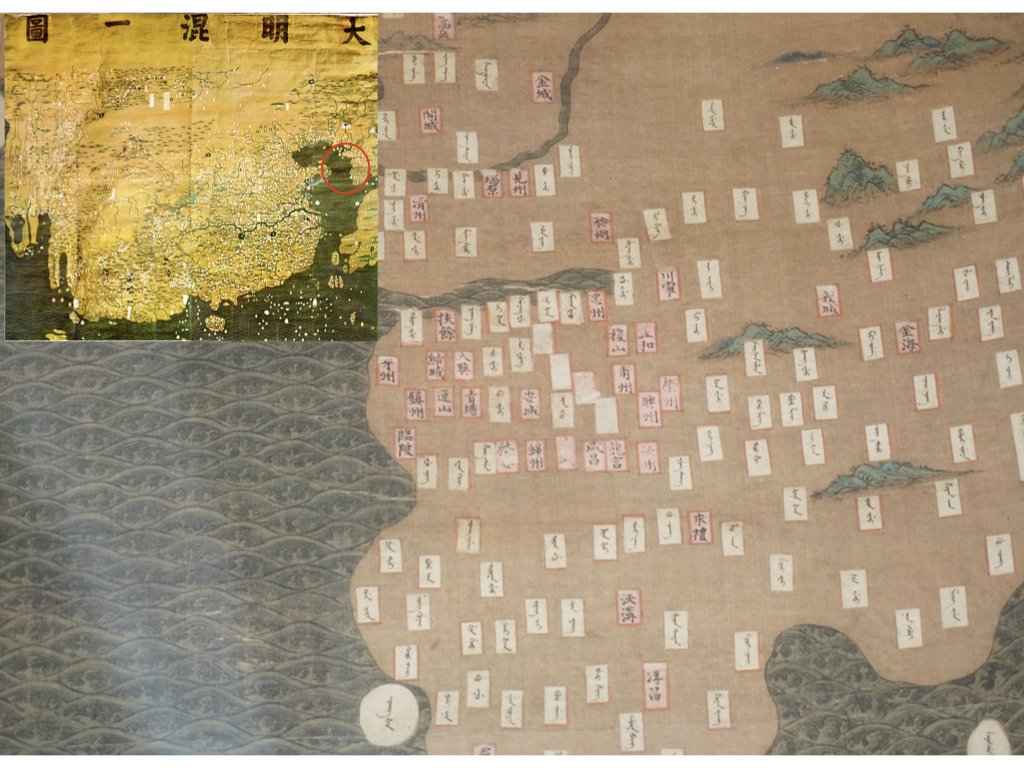

Figure 4 Synthetic map of the

Great Ming, Da Ming hunyi tu大明混一圖, original in First Historical Archives, Beijing, reprint in

Zhongguo Gudai Ditu Ji中国古代地图集 (Beijing, 1990). Facsimile from the Shanghai Museum

of Navigation 航海博物馆. Photograph by the author.

This section of the map of

the Great Ming depicts the western portion of Korea and displays the Manchu place-name

transliterations on affixed labels. In some places, over time, the labels have detached, revealing

the original Chinese text underneath.

Repairs, modifications, as well as annotations therefore, all belonged to a broad strategy of translation of cartographic artifacts first practiced in the preconquest period on the map by Li Yingshi and Ricci, then on the Map of the nine borders, and ultimately, after the conquest, on Ming maps. This demonstrates the continuity in translation across the Ming-Qing divide.

The presence of a map co-authored by Matteo Ricci in the Shenyang palace is ultimately a testament to the extent of knowledge networks in the early modern period.